In the hubbub surrounding the 50th Anniversary of the JFK Assassination, Liberia got a minor shout-out on Slate of all places, which had a little exercise of recording more than 400 places named after JFK. Monrovia's John F. Kennedy Memorial Medical Center made the map:

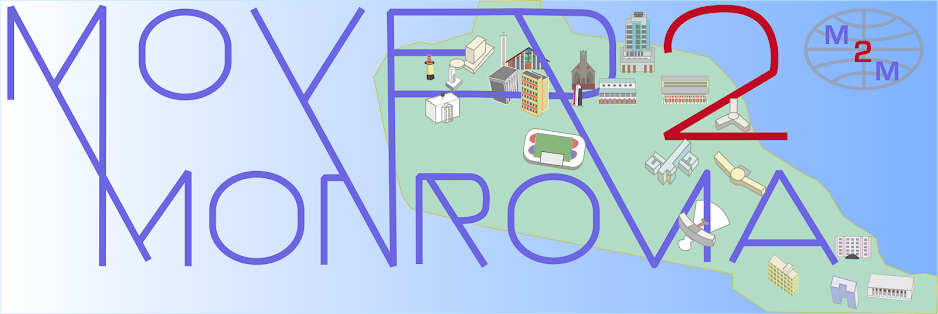

Architectural Tours of Monrovia

Saturday, November 30, 2013

Saturday, November 23, 2013

Renewed Government Effort to Wrest Control of EJ Roye

The Unity Party led government of President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf stands accused of having employed force and intimidation in the recent seizure of the grand True Whig Party (TWP) Headquarters situated on Ashmun Street in Monrovia.

In a press statement issued in Monrovia on Wednesday, November 20, 2013 by a stalwart of the TWP, Mr. Reginald B. Goodridge, Sr., said Government's seizure of the party headquarters recognized by the National Elections Commission (NEC) was not only illogical, but an affront to Liberia's emerging democracy.

Mr. Goodridge who was in a rather despondent mood while addressing the Liberian press, lashed at the UP-led administration for using the defunct People's Redemption Council (PRC) 33- year-old military Decree No. 11 in confiscating the E.J. Roye Building now reportedly leased out to an unknown business tycoon for at least US$130,000.

Terming the PRC Decree 11 as draconian, and a military instrument, Goodridge took up time to refute GOL's claims that leaders of the TWP used tax payers money to erect the EJ Roye Building.

"I want to categorically debunk such claim by the Johnson Sirleaf UP Government," Goodridge remarked, and disclosed that the EJ Roye Building, meaning TWP Headquarters, was constructed in 1965 from dues paid by partisans, prominent stalwarts, friends and sympathizers.

He said the Liberian Government has made several attempts to forcefully confiscate the building; firstly, through eminent domain to no avail and that it was on November 11, 2013 when the Justice Ministry Deputy Minister for Economic Affairs, Cllr. Benedict Sannoh, applied the PRC military Decree 11 in seizing the EJ Roye Building backed by LNP officers and GSA Director Mary T. Broh.

Goodridge explained that GOL has exhibited a blatant disregard for the due process and property rights toward its forceful seizure of the Building just as it did in the case of the National Culture Center, Kendeja, established by TWP Government, to a millionaire friend of President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf.

He said the EJ Roye Building is the legitimate property of TWP and urged government to overturn its decision and give back the Building to the party.

Accordingly, the TWP has written communications to the Embassies of the United States of America, United Kingdom, ECOWAS region, amongst others, informing them that the UP government's action constitutes a potential conflict returning to the country.

Meanwhile, the TWP in its press statement issued, called on pioneers of progressive forces in the vanguard for the promotion of multi party democracy for decades, Peace Ambassador George Weah, Cllr. Varney Sherman, political parties, LCC, Interfaith Mediation among others to speak up against "this evil that is threatening to reverse their successes."

The second report, in which the TWP leadership puts the burden on the government to prove that the taxpayer paid for the EJ Roye's construction. I've highlighted the more electric bits:

Some aggrieved partisans of the True Whig Party (TWP) have called on the Government of Liberia (GOL) to stay away from the E J. Roye Building which they say government is applying force and intimidation to seize the National Headquarters of their TWP. Speaking with journalist at the King's Building on Buchanan Street in Monrovia, Mr. Reginald B. Goodridge said such illegal act on the part of government was done without due process by personnel of the General Services Agency (GSA), backed up by a large squad of officers of the Liberia National Police (LNP) and the Executive Protective Service (EPS) on November 11, 2013.

Mr. Goodridge pointed out that GOL has not issued any official public statement on its actions, but the Deputy Minister for Economic Affairs at the Ministry of Justice, Benedict Sannoh, and the GSA Director, Mary Broh, have both stated off record that the GOL is using Degree '33' which was instituted by the Peoples Redemption Council (PRC) following the 1980 Military Coup d'Etat, which overthrew the TWP Government.

He added that there are several contradictions in the Government's actions, saying that the Government claims that it is confiscating the building as its property rights relying on PRC Decree No. 11.

At the same time, the Government has admitted that it made a deal with some individuals of the True Whig Party worth several hundred thousand United States Dollars for the privilege of confiscating the building and these same individuals recently published in a local newspaper that they had leased the building for US$130,000.00 (presumably to the Liberian Government).

This disclosure has infuriated the Ministry of Justice which had preferred that its deal with these individuals remained a secret. "I believe whenever government uses force against peaceful citizens without due process, it is a sign of weakness," Goodridge said. He added that in the wake of this illegal act, a delegation of the True Whig Party sought clarifications from Madam Mary Broh, the GSA Director General in a conference and over the telephone as to her motive, but and in her typical style, she resorted to abusive invectives, and that Madam Broh threatened that if anyone approached her on the issue of the E J. Roye Building, she was prepared to use her gun to shoot them down.

He told Broh that partisans of the TWP are no longer afraid of bullets or government's bullets, adding, "Thirty-three years ago, on that black day of April 23, 1980, when 13 of our stalwart partisans were lined up on South Beach and shot in cold blood, they were not afraid of your bullets, so we are not afraid of your bullets now; in your conscience, you know that what you are doing is wrong and illegal and your threats are simply an expression of your fear of uncertainty," the TWP stalwart averred.

Mr. Goodridge stated further that the TWP pities this government or any government that takes pleasure in using its weakness to put up a barrier around an opposition political party's institution, adding, "Know this, Madam President; instead of erecting barriers to multi-party democracy, you must break down the barriers of poverty, hunger, ignorance and disease among our youths and the Liberian people. Our people are suffering; Instead of putting food on their table and money in their pockets, you are busy taking a political party's property by force and you must break down the barriers of ethnic tensions and moral degradations in our society," TWP said.

The party furthered, "You must break down the barriers that prevent our children from going to school, the barriers that have turned our children into street peddlers and drug addicts."

Mr. Goodridge also said that President Roye was deposed and eventually killed on the very spot where the E.J. Roye Building now stands. "His body was dragged down to Slipway and dumped in the river. Propaganda was spread that he was drowned while trying to escape, but the truth is, the deposing of President E.J. Roye was Liberia's first coup d'etat, this is why the E.J. Roye Building to us is more than just a political party headquarters; it is more than just a building and it is a spiritual shrine symbolizing the fervency of our belief in justice and equality for all regardless of social, tribal or religious background."

Mr. Goodridge added that the reason that the TWP has lasted all these years is because it was built as an institution based on its Unification and Integration policies which envisaged the cohesion of every individual citizen as equal partners in the party and it did not depend on the pocket of any single individual and TWP was organized as a corporate entity that made investments and bought shares in viable corporations in order to sustain itself financially for future generations.

He added that the first attempt was made through the process of Eminent Domain, which did not succeed, then the Government informed the party lawyers that it had documentation to the effect that the National Social Security and Welfare Corporation (NASSCORP) owns the building.

He also said that it turned out that certain individuals some years ago received cash from NASSCORP in an illegal deal to sell the building, but NASSCORP could not produce any documentation to authenticate its ownership.

Mr. Goodridge concluded that the Liberian Government then claimed that the E.J. Roye Building was built with tax payers' money adding, "This has not been proven; they have challenged Madam Ellen Johnson-Sirleaf, a former True Whig Partisan, who served as Deputy Minister and Minister of Finance under the late President William R. Tolbert's government to produce any documentation such as budgetary allotment or payment voucher to show that the E.J. Roye Building was built with government's money."

Tuesday, November 19, 2013

The Collection of Liberia's National Museum: Smuggled to the US?

From a brief news item from The News, published on allafrica.com:

More than 5,800 pieces of arts and artifacts went missing from the National Museum during Liberia's 14-year civil conflict, the Director of the Museum Albert S. Markeh has revealed.

He claimed that most of these materials were looted and smuggled to neighboring countries, while some have surfaced in the African-American and Masonic Museums in the United States of America and other parts of the world.

Mr. Markeh expressed fear that retrieving these artifacts could be challenging for the National Museum because Liberia has no treaty that empowers Museum authorities to engage the American to retrieve the items.

Director Markeh, however, explained that in the absence of a treaty, the missing artifacts could be retrieved through diplomatic channels, and hoped that the Liberian Government will see the need to engage United States authorities over this issue.

Meanwhile, National Museum Director has indicated that unless something is done urgently to rehabilitate the National Museum building on Broad Street, it will collapse.While there's no question that the National Museum and its collection of historical artifacts was decimated during the War, the assertion here that these items were illicitly passed to American museums, which still hold on to them is new:

He said the building currently housing the National Museum on Broad Street is fast declining, having being built in 1862 and has not undergone major renovation.

Sunday, November 17, 2013

Building of the Month: International Bank, Broad Street

I'm going to have to get some better pictures of IB Bank's Broad Street office, the three-story building at 64 Broad Street. I'm surprised I've never taken a head-on shot of bank. This is the best I have, a low-light, late evening shot from the Palm Hotel's rooftop Bamboo Bar several years ago, with an early-model iPhone:

But recently, I did come across this astonishing photograph of the building, in about 1950 or so:

The label clearly indicates that the building was the ticket office for Pan American Airlines, if the presumption that "Pan Air" refers to the US carrier at the time. It would be especially fitting that the airline, which was such a prominent economic pillar in Liberia's economic surge which began after World War II, would establish its corporate presence in such a notable site, at the center of Liberia's business district, on Broad Street near the corner of Randall Street, which at the time was just opposite the Executive Grounds (prior the the construction of Capitol Hill, nearly all of Liberia's governmental buildings were aligned along Broad Street).

It's therefore appropriate that one of the most prominent economic connections to the United States, International Bank (Liberia) Limited, which is controlled by a private group headquartered on Connecticut Avenue in Washington, D.C., would today make use of the building as their headquarters and main banking hall.

Although smaller than some other retail banks, especially the large Ecobank office half a block away in the Episcopal Church Plaza (what was once the Chase Manhattan Bank building), IB Bank's wide reputation as Liberia's most reliable and trustworthy financial institution is reflected in its occupancy of such stately, historic building. Most likely it was a private home at some point beforehand, although its design suggests possibly that it was purpose-built for public use.

Although its deep porches have been enclosed, and recently the building was inadvisably painted in IB's butter-and-pea color scheme rather than the more elegant white, the mansion remains a gorgeous example of preserved architecture in the center of the capital. I'll have to try to research its pre-commercial history, take some better photos, and add it to the Architecture Tour.

The label clearly indicates that the building was the ticket office for Pan American Airlines, if the presumption that "Pan Air" refers to the US carrier at the time. It would be especially fitting that the airline, which was such a prominent economic pillar in Liberia's economic surge which began after World War II, would establish its corporate presence in such a notable site, at the center of Liberia's business district, on Broad Street near the corner of Randall Street, which at the time was just opposite the Executive Grounds (prior the the construction of Capitol Hill, nearly all of Liberia's governmental buildings were aligned along Broad Street).

It's therefore appropriate that one of the most prominent economic connections to the United States, International Bank (Liberia) Limited, which is controlled by a private group headquartered on Connecticut Avenue in Washington, D.C., would today make use of the building as their headquarters and main banking hall.

Although smaller than some other retail banks, especially the large Ecobank office half a block away in the Episcopal Church Plaza (what was once the Chase Manhattan Bank building), IB Bank's wide reputation as Liberia's most reliable and trustworthy financial institution is reflected in its occupancy of such stately, historic building. Most likely it was a private home at some point beforehand, although its design suggests possibly that it was purpose-built for public use.

Although its deep porches have been enclosed, and recently the building was inadvisably painted in IB's butter-and-pea color scheme rather than the more elegant white, the mansion remains a gorgeous example of preserved architecture in the center of the capital. I'll have to try to research its pre-commercial history, take some better photos, and add it to the Architecture Tour.

Thursday, November 14, 2013

Highlights of Bonham's African Art Auction, 14 November

A few hours ago in New York, Bonham's Auction House held a sale of African and Oceanic Art. As usual, I wasn't in attendance, much less buying anything, but as a small-time collector of African Art, here's a few of the highlight lots, some of which were unsold:

There were a large number of headrests in the show.

Above, Lot 82: A rare Twa pygmy Headrest from Rwanda or Burundi, sold for $5000.

Lot 106: A Kuba Headrest from the DR Congo, sold for $1250.

Lot 119: One of three beautiful Zulu headrests, this gorgeous tripod went unsold (guide price $1500)

Lot 120: Two of three Zulu Headrests, this horse-like item went for $1375.

Lot 126: Another three-legged Zulu headrest, this one went unsold (guide price $1500).

Lot 149: [The crying of lot 149!] A gorgeous Bobo bull elephant mask from Burkina Faso,

sold for $4000.

Lot 162: The only piece in the sale with a Liberian provenance, this rare Grebo door once was owned by Yale and later by the Brooklyn Museum. Amazingly, it sent unsold (guide price $8000).

Lot 182: An incredible Ijo Mask from Nigeria, sold for $8125.

Lot 187: An intricate Nupe Door from Nigeria,

possibly attributable to the carver Sakiwa the Younger, sold for $3125.

Lot 188: A gorgeous Mumuye figure from Nigeria, sold for $4375.

(profile view below)

Lot 189 A Mambila ancestral figure from Cameroon or Nigeria, sold for $6250.

Lot 210: A charismatic Pende Giwoyo Mask, from the DR Congo, with its comically solemn expression and grandfatherly beard, unsold (guide price $2500)

Lot 215: A disk-shaped Mask, used in the Kidumu Society of the Tsai group

of Teke people from the DR Congo

Lot 218: A classic; the dynamically-featured Songye Mask, this item was photographed in 1972 in the Congo whence it was sourced(below). Sold for $3500.

Wednesday, November 13, 2013

Employment and Growth

John Page, a Senior Fellow at the Brookings Institution, points out in a post from this Spring, titled Africa's Jobs Gap, that "Africa Rising" does not necessarily mean Africans are rising. Employment statistics are not encouraging:

Eighty percent of job seekers find themselves in informal employment, self-employment or family labour. These are not good jobs...

Africa’s lack of good jobs reflects a feature of the region’s growth often overlooked in accounts of its success: Africa’s economic structure has changed very little. The region’s share of manufacturing in GDP is less than one half of the average for all developing countries, and it is declining. The sources of Africa’s recent growth – improved economic management, strong commodity prices and new discoveries of natural resources – are not job creators.

While manufacturing is most closely associated with employment-intensive growth, there are also ‘industries without smokestacks’ in agriculture and services that can create good jobs. Investors in these industries, however, do not see Africa as an attractive location. Domestic private investment has remained at about 11 percent of GDP since 1990. This is well below the level needed for rapid structural change. Foreign investment is overwhelmingly in oil, gas and minerals. Industry in Africa has declined as a share of both global production and trade since the 1980s...

For poor countries the export market is the main source of industrial growth. Africa has had little export success: manufactured exports per person are less than 10 percent of the average for low income countries. Breaking into non-traditional export markets will demand a coordinated set of public investments, policy reforms and institutional innovations more characteristic of Asian than African economies.

Tuesday, November 12, 2013

Employment and Survival

The on-going pehn-pehn ban is causing a confused situation in Monrovia. As referenced in a blog post on The Economist Baobab column filed today, just what the young motorbike drivers are supposed to do without their former source of income seems to be just one of the several major issues not being recognized in this situation, especially when many in this group may have been actors in the former conflict.

This seems like to a good time to quote from an article on remarks made by the European Commissioner for Development, Andris Piebalgs, speaking at an international youth job creation summit in London earlier this fall:

This seems like to a good time to quote from an article on remarks made by the European Commissioner for Development, Andris Piebalgs, speaking at an international youth job creation summit in London earlier this fall:

Sub-Saharan Africa’s relatively low youth unemployment rate of 3 per cent, compared with the 50 per cent in some European countries, disguised the scale of the issue…

“Most of the jobs are in the grey or informal economy. They work to survive, or to work on their parents’ farm,”

At the same time, their expectations were rising and many of them saw economic growth rates averaging 4.5 per cent as inadequate compared with the 10 per cent achieved by some other emerging economies.

“If these countries get a positive growth agenda, I believe they will come over the hill,”

“In a worst-case scenario, there would be instability, conflict between groups and a lot of refugees in all directions.”

Thursday, November 7, 2013

The Problem is not the Pehn-Pehn

"These guys are like suicide bombers," my Liberian friend sighed from behind the wheel as our car slowly made our way through central Monrovia recently. Outside of our vehicle, an kamikaze-like swirl of motorbikes flitted within inches of our car, seeming to bounce off the fenders of the vehicle in front. Any gap between cars of more than a few feet was ample territory to be conquered, and was soon filled with buzzing bikes. In what has become a typical scene on Monrovia's streets the motorbikes, known locally as pehn-pehns (or pen-pens), for the sound of their endlessly repetitive bleating horns, created a chaotic choreography set to their own cacophony, making the movement of the car down the block stressful and difficult.

Pehn-pehns have never been widely beloved among Liberians, but seem to be particularly loathed by those Monrovians who have the luxurious option of moving around by private vehicle. Even among Liberians who take pehn-pehns regularly, pehn-pehn operators are held somewhere between a head-shaking disregard and a teeth-clenching outrage. There seen as lawless, senseless. Although the streets of many African cities swarm with motorbikes, they are a particularly notable feature of Monrovia, a city whose contemporary crowding seems most noticeable in three expects: its sprawling suburbs, its overstuffed slums, and its standstill street traffic.

As Monrovia's economy has burgeoned in the last few years, the capital's once-potholed and empty main roads, now smoothed over with recent tarmac, have filled with vehicles, resulting in crawling congestion during daylight hours, particularly during an increasingly-epic rush hour along the city's spine, Tubman Boulevard, from the city's eastern residential fringe into the commercial center. While these jams pale in comparison to the legendary Lagosian go-slows or Accra's dawn-to-dusk parking lots, in the last few years have Monrovians partaken in that most mundane of moans: complaining about the endless traffic.

Partly, geography is to blame: stretched across a long peninsula, Monrovia now spills across the swampy plains to its north and east. Connected by a single road, the city is poorly-equipped to handle commuter traffic from its historic central area to the now-burgeoning suburban areas such as Paynesville and Duazohn, which stretch for as much as twenty miles from the heart of the city. The traffic problem worsens each month as each container ship full of cars unloads at the city's Freeport, and has grown noticeably worse, somewhat ironically, with the addition, starting last year, of a series of low-function traffic lights at major intersections along Tubman's length, which seem to ensure bottlenecks along the city's single street.

Packs of Pehn-pehns dart dangerously through this traffic, riding the double-yellow line down the center of Tubman as if they were merely inches wide, "playing chicken" with oncoming traffic as they rush head-on towards a line of side-view mirrors. There's no question its dangerous and annoying. It's also envy-inducing to see travelers zipping past standstill vehicles, their ride costing less than a dollar.

What's less disputable is that pehn-pehns, despite their dangers and annoyances, constitute an essential form of affordable transportation for a great number of Monrovians, and are therefore an irreplaceable component of the transport infrastructure of a fast-growing city where there are few forms of public transport. Even if Liberia's National Transit Agency doubled the fleet of Indian-donated buses that ply Monrovia's streets, pehn-pehns would remain a vital form of transport for the vast majority of the city. The result is an inverse relationship between their irreplaceability and the scorn they engender.

The demographics of the drivers aside, an unaddressed issue in the loathing the pehn-pehns bring, is that their role in the city's transport system has not been formalized and integrated thoughtfully. The placement of traffic lights at many intersections has further impeded traffic movement; many big intersections are crowded and impassible not necessarily because of the volume of automobiles, but due to curbside taxi and pehn-pehn parking areas, where commuters switch between shared taxis and motorbikes to continue their journey. These intermodal zones are not officially designated or set aside, and so slowing taxis and rows of parked motorbikes block a lane, causing cars to squeeze by.

Image courtesy FrontPageAfrica

Authorities in Liberia have often taken an adversarial approach to the pen-pen drivers and their representatives, seeming to transform the general public's dislike into draconian (and vague) regulations. In the last few years, the government has imposed a series of increasingly-aggressive restrictions on pen-pen movement, of which last week's sudden ban is the most severe. In 2011, the Liberian National Police imposed a night-time curfew for motorbikes, supposedly in to thwart armed robbers from their get-away vehicles of choice. Perhaps surprisingly, this curfew has held.

"Our biggest problem is motorcyclists. The Motorcycle Union is growing almost every day. You have new riders coming on the streets every day, and many of them are not trained. They do not understand the traffic rules, and they don't want to protect themselves," --Minister of Transport Tornorlah Varpilah, October 29thIn a city still mostly devoid of formal or even informal employment opportunities for the undereducated youth of the city, hopping behind a pehn-pehn and immediately collecting 20 or 50 LD per ride is an all-too-rare means to find enough to eat rice each day, if not a rung on the ladder to any kind of economic self-sufficiency.

I've had my run-ins with pehn-pehns, quite literally: for every 18 months that I've lived in Monrovia, I've had a motorbike crash into my car, sometimes while I was driving. No one has been hurt, thankfully, but the aftermath of each has been a highly unpleasant confrontation in which I was threatened with physical violence and monetary pay-offs were demanded, even though it wasn't my fault that my vehicle was hit and damaged. I wouldn't recommend the experience to anyone. Nearly every car trip in the city features an aggressive encounter with a motorbike, whether a close cut-off or near-collision. It is this disregard for the rules of the road that partly explains the widespread disdain for pen-pen drivers, but equally, I think, is the class distinction between the possibly-ex-rebel drivers and the rest of the public, be they office workers or ministers. Many Liberians abhor disorderliness, which the risky, careless motorbikes seems to embody.

I am fully supportive of regulations for the motorbikes, including those that are being debated this week: ensuring that drivers are licensed and trained, that helmets are worn, and safe driving is practiced. But this latest edict, effectively outlawing most journeys by motorbikes, seems not so much an attempt to improve safety but to rid Monrovia's auto lanes of a pestering annoyance of having to share the road with pehn-pehns. This has its connotations in the canyon-like class divides in this city, where the better-off openly disdain their poverty-stricken fellow citizens, who struggle to get by. Rather than decreeing that motorbikes (and the people that operate them and reply on them) disappear, Monrovia would be better off if it developed a comprehensive plan to carve out dedicated space for the city's motorbikes, and their users, and recognized how both are vital and beneficial to this city and its residents.

Monday, November 4, 2013

New Air Cote D'Ivoire Flights to Monrovia

Looks like a posted the last report on regional airline flights a bit too soon. Just today, Air Cote D'Ivoire announced a revised Winter schedule, which includes a brand-new Abidjan-Monrovia-Freetown service, three-times per week:

Interestingly, the schedule refers to MLW, or Spriggs-Payne Airport, rather than RIA (here's one saying it is Spriggs, here's another saying its an Airbus to Robertsfield) Whether this is the actual choice of airport isn't certain as there is no other information on the airline's website. Also not clear what aircraft will be used, although it will likely be an Embraer 170 turboprop. Presumably, given the regional rules on flights, Air Cote D'Ivoire will be allowed to carrying passengers between Monrovia and Freetown.

* Abidjan – Monrovia – Freetown NEW 3 weekly service from 22NOV13

HF762 ABJ1200 – 1325MLW1405 – 1450FNA 319 257

HF763 FNA1530 – 1615MLW1655 – 1820ABJ 319 257

Interestingly, the schedule refers to MLW, or Spriggs-Payne Airport, rather than RIA (here's one saying it is Spriggs, here's another saying its an Airbus to Robertsfield) Whether this is the actual choice of airport isn't certain as there is no other information on the airline's website. Also not clear what aircraft will be used, although it will likely be an Embraer 170 turboprop. Presumably, given the regional rules on flights, Air Cote D'Ivoire will be allowed to carrying passengers between Monrovia and Freetown.

Friday, November 1, 2013

Air Mano River Union?

A bit of a strange, and typically vague press report came out of the recent meeting between the Transport Ministers of the Mano River Union (Liberia, Sierra Leone, Guinea and Cote D'Ivoire) that stated, in part:

The Ministers of Transport of Liberia, Sierra Leone and Guinea have resolved to establish a common airlines to connect the three countries and ease the difficulty being experienced by inhabitants of the sub-region because of the absence of connecting flights.

It should be noted that presently none of these three countries has any domestic airline, unlike Ivory Coast, with its recently re-launched state carrier, Air Cote D'Ivoire. Perhaps that's why the MRU's newest and largest member state (which also does not straddle the Mano River) is not listed among the countries seeking to 'establish a common airline.'

The impracticalities of this scheme are evident: aviation anywhere is a costly endeavor; even in low-competition Africa, continental giant Kenya Airways struggles to yield a profit. In the region, privately-backed, would-be Sierra Leonean state carrier Fly 6ix went bust with little fanfare, while news of an Arik-backed or government-back successor have gone silent.

The region remains a tiny market for commercial flights, with fewer seats departing Liberia in a week than are filled at most major airports in a quarter of a single hour. Furthermore, there is still very little need to connect the Mano River Union capitals with one another, much less for domestic flights. Since Brussels Airlines changed its schedule earlier in 2013, there has been no scheduled service between Abidjan, an urban center of 5 million, and Monrovia, just 2 hours away (Brussels airlines stops in Freetown as of last month). Likewise, Conakry and Monrovia were initially linked by Air France's service which it began in 2011, but that has now switched to a stop in Freetown. British Airways also flies to Freetown, although it doesn't have rights to drop passengers from Liberia in Sierra Leone. Despite all these widebody fights, there are still more frequencies to further-away Accra than next door Freetown.

ASKY Airlines, launched in 2009 by Ethiopian Airlines, and based out of Lomé, dominates scheduled flights across West Africa, albeit with tiny turboprops making a handful of flights a week, few of which hopscotch the Anglophone/Francophone checkerboard of West African countries. In April, a flight from Monrovia to Abidjan took 6 hours, as the only routing was on ASKY from Monrovia to Accra to Lomé, to a change of planes to reverse directions to Abidjan. This is the result of the current state of both the economics and regulations of the region, and ASKY has been successful in part because it boasts no particular national affiliation. Although national flag carriers will always be a point of pride for governments, they are expensive and impractical, especially for under-budgeted, underdeveloped countries.

The Ministers of Transport of Liberia, Sierra Leone and Guinea have resolved to establish a common airlines to connect the three countries and ease the difficulty being experienced by inhabitants of the sub-region because of the absence of connecting flights.

It should be noted that presently none of these three countries has any domestic airline, unlike Ivory Coast, with its recently re-launched state carrier, Air Cote D'Ivoire. Perhaps that's why the MRU's newest and largest member state (which also does not straddle the Mano River) is not listed among the countries seeking to 'establish a common airline.'

The impracticalities of this scheme are evident: aviation anywhere is a costly endeavor; even in low-competition Africa, continental giant Kenya Airways struggles to yield a profit. In the region, privately-backed, would-be Sierra Leonean state carrier Fly 6ix went bust with little fanfare, while news of an Arik-backed or government-back successor have gone silent.

The region remains a tiny market for commercial flights, with fewer seats departing Liberia in a week than are filled at most major airports in a quarter of a single hour. Furthermore, there is still very little need to connect the Mano River Union capitals with one another, much less for domestic flights. Since Brussels Airlines changed its schedule earlier in 2013, there has been no scheduled service between Abidjan, an urban center of 5 million, and Monrovia, just 2 hours away (Brussels airlines stops in Freetown as of last month). Likewise, Conakry and Monrovia were initially linked by Air France's service which it began in 2011, but that has now switched to a stop in Freetown. British Airways also flies to Freetown, although it doesn't have rights to drop passengers from Liberia in Sierra Leone. Despite all these widebody fights, there are still more frequencies to further-away Accra than next door Freetown.

ASKY Airlines, launched in 2009 by Ethiopian Airlines, and based out of Lomé, dominates scheduled flights across West Africa, albeit with tiny turboprops making a handful of flights a week, few of which hopscotch the Anglophone/Francophone checkerboard of West African countries. In April, a flight from Monrovia to Abidjan took 6 hours, as the only routing was on ASKY from Monrovia to Accra to Lomé, to a change of planes to reverse directions to Abidjan. This is the result of the current state of both the economics and regulations of the region, and ASKY has been successful in part because it boasts no particular national affiliation. Although national flag carriers will always be a point of pride for governments, they are expensive and impractical, especially for under-budgeted, underdeveloped countries.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)